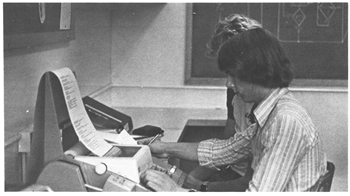

Circa 1974: my snapshot of some comrades, armed with a teletype.

Computing in the early Seventies

by Greg Bryant

Yellow paper. Cheap, newsprint-like yellow paper from continuous rolls. When

the teletype finished typing, you ripped off the paper against a plastic shielding,

which never cut quite evenly. These yellow pieces of paper, coming from rolls,

always wanted to roll up again, seemingly with life-goals of their own. Always

we tried to hole-punch and put these yellow cut-up sheets into notebinders,

but it was never satisfactory. Our notebooks and folders always puffed with

these curving sheets, amusing normal onlookers.

Then there was that light yellow paper-tape, for storing data and programs,

with a little perforated track running down it, and shot through with scattered

data holes. The confetti that resulted from punching tape we called holes,

and like sand, they would get everywhere. They collected in a plastic

bucket, when this functioned properly. Very tempting when they accumulated.

We incorporated them into school pranks in endlessly imaginative ways. Stuffed

down the shirt. Sprinkled over someone's lunch. Peppered into textbooks. Seemingly

blown from the nose when sneezing. Presented to the professor, with sleight-of-hand,

as the results of a chemistry experiment. What delightful students we were.

I remember one teacher actually crying in front of the class, probably triggered

by such a prank, but really the result of some cumulative frustration, both

inside and outside of school. The awkward moment sticks with me because it was

something absolutely no one was socially prepared for. Teachers were supposed

to smile thinly, make a funny comment, and continue. On the whole the students

at my High School were bound for success, probably making discipline easier

to administer with a smile. On the other hand, this made the atmosphere congenial

enough that we generally had the run of the place.

I have no idea why I first sat down at a teletype. Probably my youthful obsession

with science and science fiction, not my only childhood interest, but one most

likely and mysterious for a youth growing up in the 1960's. I was bombarded

with massive science education campaigns nearly from birth, inspired by a kind

of hysterical reaction to the USSR launch of Sputnik. The subtle shaping of

young minds, and the moving of the best minds into science and technology, was

considered necessary for the winning of the cold war, and later for the economic

wars. The successful brain-drain into high-tech makes me part of the "lost

generation" of the cold war.

When I first wrote a program that did more work than I would, I was hooked.

To someone who had never built much of substance, which applies to many middle

class educated children, a computer program seemed to actually do something,

and with very little sweat on the programmer's part. This mix of pride in accomplishment

and realization of power drew me in.

Why had I never created anything that had given me such intense satisfaction?

I had written articles and taken photos for newspapers, published mimeographed

newsletters, starred in school plays, completed little science exhibits for

school, collected rocks, started a Star Trek fan club the year it began, and

energetically made sure I was the center of everyone's attention one way or

another.

So why were computers more satisfying? I still remember the feeling, a power

to make something else behave according to one's commands. The Teletype was

such a clunky, sturdy mechanism, that it almost seemed to be a robot, a limited

one, clattering and vibrating with enthusiasm, leaking yellow paper everywhere.

A slave? Well, I certainly didn't think of it in those terms. It was a palpable

result of my power to create. An active beast, not just clay or sheet metal

badly manipulated in shop class. Perhaps if we had built some other kinds of

machines in school, or been given some other exposure to quality training, I

would have become similarly hooked. A rube goldberg machine, a hand-cranked

music box, a bicycle, a fence, even a garden or having children (though that's

more work) would have given me equivalent satisfaction. But I didn't make those

things in my school, and my high-brow ambitions possibly would have kept me

away from such productive pursuits had they been available. There was a certain

roughness in people involved in such things, I felt at the time, and I am quite

sure that I didn't want to be tainted with the association. I had built models,

and things out of lego, but they didn't seem part of the real world,

or useful in any way. It was to be keystrokes instead of tools. My first

engineering satisfaction came from a computer.

Computing didn't occupy much of my time. Theatre, journalism and other science

took a great deal more. And going to the university library, just browsing,

looking up things whimsically. But the computer room, eventually soundproofed,

which started as just a corner of a math study area, was a special place. Many

people used it, but only a handful of us, mostly boys, were proficient. We'd

hang out there, and help people, especially girls, get over the hurdles. That

a subculture of assistant instructors basically invented itself must have been

appreciated by the teachers.

The computer attached to our teletype lay far away from the actual school grounds.

If it hadn't I'm sure we would have gathered in its even noisier machine room,

in order to find its innermost secrets. As it was, we would find priviledged

user accounts and snoop around in other people's mail, even into some teaching

accounts. But we never found anything very interesting. We could not really

change grades from where we were. We tried to collect lists of everyone's passwords,

however. My friend and colleage Geoff got terrific grades and so was apparently

considered more trustworthy. He was given priviledged accounts, whose powers

he then passed on to his closest friends when he was in the right mood.

And then we began to visit the university's computers. In 1974 or 1975 the university

had an incipient computer education program, and it's enthusiastic "computers

are the best teachers" acolytes, including the founding chairman of the

department, held a Fortran class for gifted young computer kids.

Besides pervasive piles of green and white print-outs, there was another kind

of yellow paper: buff-colored IBM computer cards, one for each line in a computer

program, with, usually, yellow stripes along the top where the carefully typed

lines could be read. Creating these cards was ridiculously difficult, using

an unforgiving keypunch system that wouldn't let you correct a typo: the hole

was already there. But with discipline, you can overcome the problem. To this

day, if I really want to, I can always type without a single mistake. Albeit

slowly.

We became bored with this tiresome creation of cards, and so went upstairs

where a batch of familiar teletypes were attached to a timesharing computer

made by Digital Equipment Corporation. Here we were more in our element, or

so we thought. Quickly we began stealing the passwords of trusting students.

They didn't always understand the twist on everyday courtesy and common sense

that assigns a password some value. The computer was part of the school, these

kids were students, so what if they know my password?

The accounts were paid for invisibly, interdepartmentally, so no student thought

computer time had value. They should have been right: computers seem quite permanent,

and, rather like a couch, common sense would not assign value to computer time

in the same way as you would to a person's time. But computers are always falling

apart, and in what is euphemistically called maintainence, people's time must

be paid for. But at this stage of the game, people didn't really see that. They

had been isolated from the machine and had no sense of the huge monetary and

personnel resources it required. So we acquired passwords easily.

Quickly we got into, what seemed like, very serious trouble. We typed out many

things on the teletypes to try to find how the system worked. One helpful and

knowledgable fellow pointed out that we could print this out much more quickly

using a hidden, high-volume printer on the first floor, and as a demonstration

he printed what amounted to an entire manual for us.

One young colleague followed up on a thought we had, to print out the entire

computer memory, known as the "core" in those days, after both the

two-state magnetic donuts arrayed in the machine, and the centrality of memory.

We guessed, wrongly, that we could find passwords that way, and perhaps change

student grades, unfortunately only at a university we weren't yet attending.

The enormous, unreadable printout of zeros and ones was immediately detected,

being three feet high, and our secret ring of spys was found out.

We were all interviewed separately. The financial damage actually was only about

$4 per boy. But that wasn't the point. We were the cream of the young computer

crop, and we shouldn't go around stealing computer services. This was all a

bit confusing. They wanted us to explore this new technology, but only in prescribed

ways. But the nature of exploration for us was in pushing the limits. We went

along, and apologized, but suspected some contradiction which only the adult

world seemed able to concoct. The computing world didn't seem particulrly moral,

after all. We were being given the third degree for what we did: they

weren't particulalrly interested in why. Certainly they tried to scare

the bejeezus out of us, threatening with jail, reform school, a ruined life,

and, as I remember most seriously but rather subtlely, "all those brilliant

people you could have associated with but who now think of you as a delinquent"

or some such obsequious-tainted warning. The whole episode had frightened and

enraged me, I think, in equal parts. I wasn't used to being rebuked like that.

Two years later I was hired into this computing center by the same people who had rebuked me. They remembered the incident as being not in the least bit serious. Adults must be a bit more careful about simulating totalitarian behaviour.