Great Basin Archaeology

at Steens Mountain

The University of Oregon Field

School

[now The University of Oregon Archaeological Field School]

and the Steens Mountain Prehistory Project

Summer 1979

by

Greg Bryant

December 29, 2002

My minor was archaeology. It's been an interest of mine since prehistoric times.

My first real dig was in a desert: a joint project run by the University of Oregon and the University of Washington. The subject: aboriginals at the end of the pleistocene, about 10,000 years ago. The lucky bastards lived as free individuals, around the edge of a receding pleistocene mega-lake -- located in what is now The Great Basin. The Great Salt Lake is the only significant body of water remaining from that vast sea. But, in addition, there's a seasonal alkaline pond in the Alvord desert, a fresh-water migratory-bird paradise at Malheur Lake, breath-taking gorges in the Steens mountains, and stunning valleys hosting the Alvord and Catlow deserts. When you stand in those valleys, it's not difficult to imagine the original Great Basin lake.

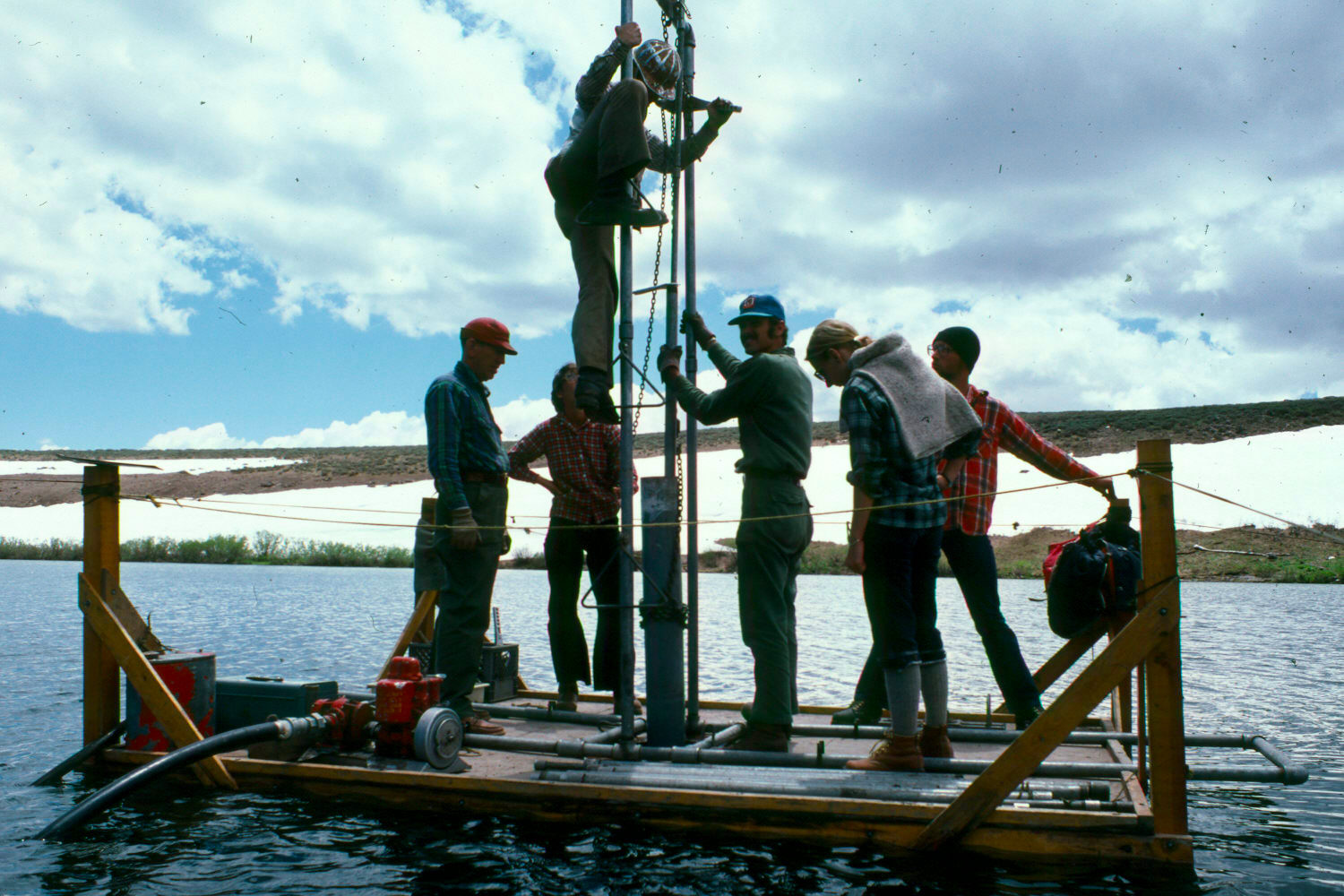

We dug and differentiated strata in caves that rimmed the former lake. We surveyed the deserts in transects, and mapped tool-making sites. We drilled cores at the bottom of an icy mountain lake. And we partied. 40 students -- what could be expected? I remember that I shared a tent for two months with three women, but because men of the time were culturally hampered, I have only a recollection of their surface characteristics: a quiet and disheveled blonde, a talented japanese student, and a funny brunette.

For some reason, I typically wore a thick, white canvas karate outfit, known as a do gi or gi, in the field. I think the top is in the photo below. Ah, I remember the reason: I believed it was perfect for the desert -- far from the skin, insulating, and reflective white, it kept me cool, yet the material was sufficiently thick to keep me warm after sunset. And I could 'workout' at the drop of a hat! Speaking of which, I also wore a floppy terry-cloth hat, which I'd ordered after seeing it in one of the Whole Earth Catalog publications. Good for soaking up sweat, it provided extra cooling if you dipped it in a mountain stream, like the one running by our main site. The gi became very dirty, very quickly, and being white, it was hard to wash well with no laundering facilities. If it wasn't for my chatty and introspective character, people would have thought I simply couldn't look after myself. They may have thought this anyway, in retrospect. I was probably considered just an eccentric know-it-all. But I did the work, and and there was social harmony, most of the time. The environment ensured this. We needed to be a tight-knit group.

The Alvord desert.

You know, I was tempted to repeat something 'impressive' from my opening description, like "I took core samples of pleistocene sediment from the bottom of a mountain lake". But today, I see a photo like the one below, of a hard-working professor [pioneering palynologist Peter J. Mehringer, Jr., whose father won an Olympic Gold Medal in wrestling 47 years earlier ...] clambering over a drill-rig, day after day, suspended over ice cold water, and I think "how nice of him to make these archaeology students feel like they're being useful." Because we were not terribly functional on this raft -- falling off, dropping tools, asking pesky questions at critical moments ... very draining I'm sure. But now, I find it inspiring, that these accomplished middle-aged folks put up with us, and ran a field school for us. It takes such hard work and willpower to present what we know to the next generation.

On the right, Don Grayson, co-director of the 1979 dig.

Don Grayson captures Mount Mazama's ash strata -- remains of the eruption of that formed Crater Lake.

I don't really understand how we were sent to this abandoned plateau ranch -- a site called Lauserica. It was beautiful, surrounded by fields of sharp-to-the-touch mosses that looked like lush, natural lawns. I believe it was just me, another fellow, and three women -- all undergrads. We were dropped off and stayed for a week, to survey a nearby hill. All the buildings were roofless, so we set up a small one-pole army tent and piled in there for some surprisingly cold nights. And then, one of those nights, an endless, apocalyptic storm blew through ... with continuous massive rain, wind, and lightning for hours and hours. We should have been killed -- we were at the highest point (by thousands of feet) and our tent had a metal rod running down its center! We couldn't go outside, since there was a good chance our tent would get washed or blown off the mountain. We pressed back against the soaking wet walls of this tent, as far as possible from the cast-iron pole, which was electromagnetically possesed and vibrated violently like an off-kilter washing machine. The level of static electricity in the tent made our hair stand on end. A terrific learning opportunity!

The tent.

The morning after the storm.

This is Mel Aikens in 1979. C. Melvin Aikens was director of the field school; later anthropology department head at the U of O; famous for countless studies of the western US and Japan; a very dedicated teacher and scientist; and a charming fellow. The Field School is a wonderful program, pedagogically idealistic, salutary and fun. It was launched by Luther Cressman, a pioneer of western archaeology, who founded the U of O Anthropology department out of the Sociology department in the 1930's. Cressman was the first to dig in these Steens mountain caves -- actually, we re-broke soil in several sites that he'd closed some 50 years earlier. Amazingly, Cressman was still around, and came to visit us at the site -- only one time, if I remember correctly: I saw him over so many years and events at the U of O, that it's hard to precisely recall. He didn't visit the field school as much as in the past: he was born in the 19th century, after all. He was just beginning his memoirs, which included his marriage to Margaret Mead. Coincidentally, if I might be self-indulgent here, I ran into Margaret Mead as a kid. Growing up in New York in the 1960's, I went to the 'American Museum of Natural History / Hayden Planetarium' whenever I could persuade an adult to take me, possibly hundreds of times. Many kids my age did this. I went to lectures, films, took classes ... Mead was the busy star of the museum at the time, and was everywhere, it seemed. She also ran what I can only describe as social laboratory experiments -- which I remember because, as I was looking at the 'live insect exhibit' one day, her assistant pulled me into what later we might have called a multicultural discussion for kids, which she was facilitating, in a little gathering room with color-carpeted walls. I vaguely remember telling Cressman this story, and he told me he'd written as essay about Mead, which he wished more people would read. I found Cressman's essay about Mead -- and about their mentor, the great ethnicity leveller Franz Boas -- responding to historians who apparently forgot to talk with anyone who was there. I post it here on the web as a modern interpretation of his wishes.

When I think of people like Aikens, Grayson, Mehringer, Cressman, Mead, and Boas, my metabolism slows in silent admiration for what seems, from here at least, their impossibly long, unflagging effort and spirit: to study, to document, to teach, to explore. As a youth I was curious about their efforts, but was skeptical and irreverant: that's part of the game between the young and their elders. But their influence, and the cumulative influence of many people like them, trying both to do something good and to discover something about the world, has kept me going all these years.

Mel Aikens sifting:

Mel Aikens and Don Grayson.

My quiet tent-mate, struggling awake. Our days started at 6am, because by 3pm it was too hot to work.

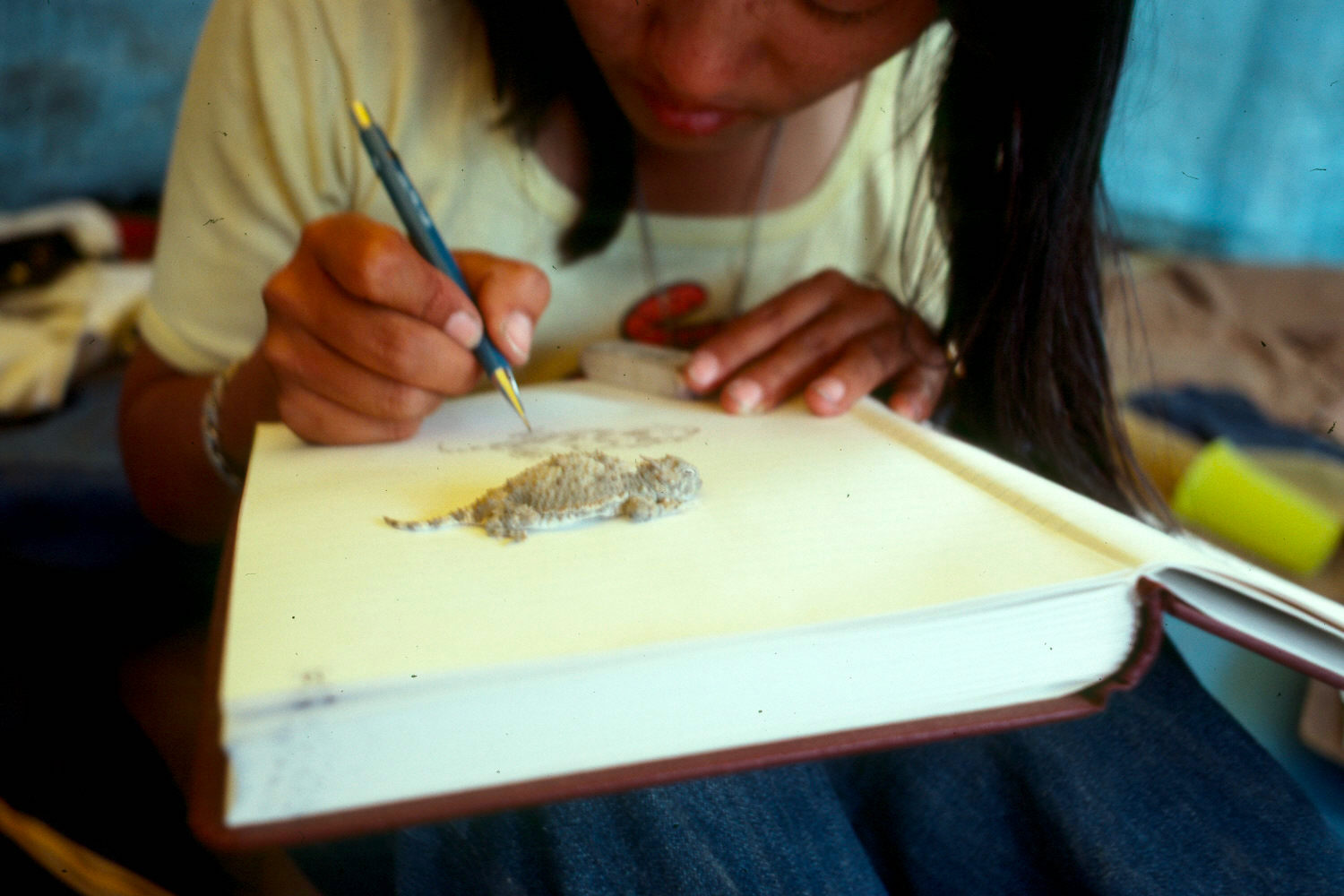

The Japanese student, another tent-mate, sketching one of the best live modeling performances I've ever witnessed -- it still astounds me that this wild lizard, unmanipulated, decided to remain as still as a rock for the duration of this figure study. [For the record, it's a phrynosoma platyrhinos, often called a 'horny toad', even though it's a reptile, and not an amphibian].

This is 'the lab'. If you were tired or sick -- from heat stroke for example -- you would work here for a week's rotation. It was tedious labelling and recording work, but also the coolest job. You could get comfortable at main camp, and catch up with your chores, and fix stuff around the camp that everyone complained about but had no time or energy to address. We listened to music tapes -- I remember the Notorious Byrd Brothers album, The Doors, Claude Bolling, David Grisman, the Holy Modal Rounders. We took luxurious lunch breaks, welcomed visiting scholars, and talked about everything. So very cozy.

I put this photo here because, maybe I'm a nut, but, since I was young, I've always relished the idea of a "Lab Library". Something stocked well for those late nights waiting for experimental results, or for those endless months doing field work in the deepest wilderness. A kernel of literature and learning, and a well-used repository for a small community. It's a funny notion to be attached to, but it has so much resonance for me, that I can see its influence throughout the years. Not the most important thing, surely, but a non-trivial and sweet thing, nonetheless.

More soon,

Greg Bryant

Note: William Loy, a strikingly good-natured professor of Geography, and founder of the Atlas of Oregon, gave me a ride back to Eugene, over almost 500 miles, from this 1979 expedition, which he was visiting while traveling with his young son. The key Geographer of Oregon was obviously the best-informed person I could ever traverse Oregon with. He had a copy of 'Oregon Geographic Names' (a historic gazeteer) in his car, and I remember distinctly feeling that maps and reality were merging for me, as he described our ascent to, descent from and traversal of different biological habitats and geological regions. Although I'm a naturally curious person, and grilled him constantly during this long journey, I think he very much influenced the way I travel today, with an eye on economics, politics, culture, geology, weather, history -- with a strong appreciation of how hard it is to actually know these things, and of how much fun it is to try! Bill Loy died last weekend (I'm writing this addendum on November 20, 2003). A well-lived life, from what I knew of it.