Eugene Magazine Features (Winter 2006)

Two to Tango

Lovers of the seductive Argentine Dance have brought new style to Eugene

By Ariel Olson

IT'S SATURDAY NIGHT at the Tango Center on West Broadway. Multicolored spotlights shine on a ring of small café tables; the dance floor is illumined by a single red light bulb hanging from the unfinished ceiling. Traditional tango music-a gentle piano, the melodic bandoneón-whispers through the door and calls passersby to investigate. Dancers of all ages pack in. Their enraptured movements, at first high energy, become gentler as the evening wears on, but no less captivating to watch.

If you think social dance is dead, you haven't visited the Tango Center, the hub of Eugene's burgeoning tango scene.

From the outside, the nondescript studio is marked only by a white sign with the word “Tango” printed in simple black lettering. Inside, the former pool hall has been stripped down to the bare necessities: a few mirrors, several couches huddled in a dimly lit lounge area, a refrigerator with beverages. Vintage tango posters and outdated milonga announcements line the plain white walls. It's no hotel ballroom, but to the self-professed tango junkie it's Eden.

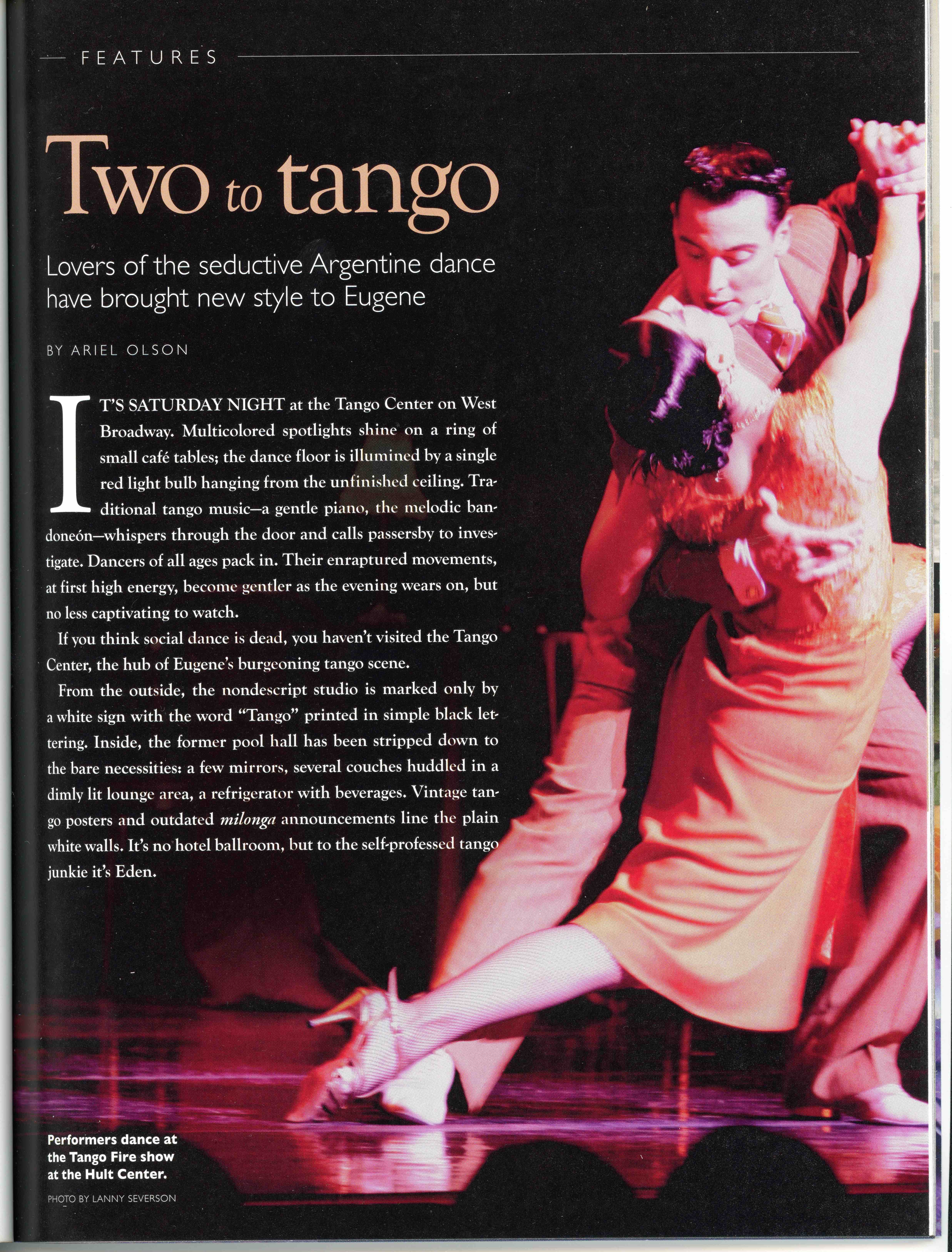

Photo: Performers dance at the Tango Fire show at the Hult Center.

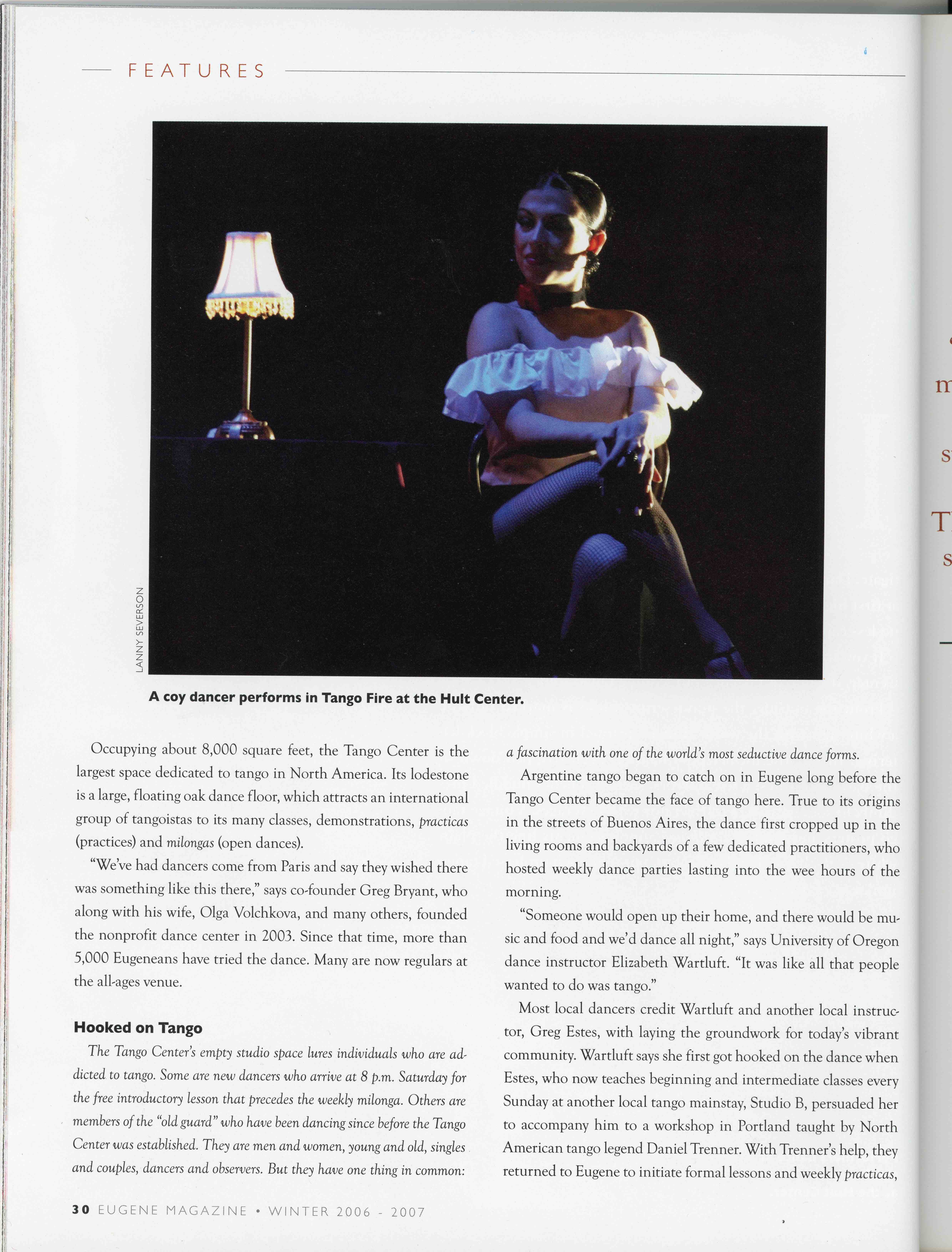

Photo: A coy dancer performs in Tango Fire at the Hult Center.

Photos by Lanny Severson

Occupying about 8,000 square feet, the Tango Center is the largest space dedicated to tango in North America. Its lodestone is a large, floating oak dance floor, which attracts an international group of tangoistas to its many classes, demonstrations, practicas (practices) and milongas (open dances).

“We've had dancers come from Paris and say they wished there was something like this there,” says co-founder Greg Bryant, who along with his wife, Olga Volchkova, and many others, founded the nonprofit dance center in 2003. Since that time, more than 5,000 Eugeneans have tried the dance. Many are now regulars at the all-ages venue.

Hooked on Tango

The Tango Center's empty studio space lures individuals who are addicted to tango. Some are new dancers who arrive at 8 p.m. Saturday for the free introductory lesson that precedes the weekly milonga. Others are members of the “old guard” who have been dancing since before the Tango Center was established. They are men and women, young and old, singles and couples, dancers and observers. But they have one thing in common: a fascination with one of the world's most seductive dance forms.

Argentine tango began to catch on in Eugene long before the Tango Center became the face of tango here. True to its origins in the streets of Buenos Aires, the dance first cropped up in the living rooms and backyards of a few dedicated practitioners, who hosted weekly dance parties lasting into the wee hours of the morning.

“Someone would open up their home, and there would be music and food and we'd dance all night,” says University of Oregon dance instructor Elizabeth Wartluft. “It was like all that people wanted to do was tango.”

Most local dancers credit Wartluft and another local instructor, Greg Estes, with laying the groundwork for today's vibrant community. Wartluft says she first got hooked on the dance when Estes, who now teaches beginning and intermediate classes every Sunday at another local tango mainstay, Studio B, persuaded her to accompany him to a workshop in Portland taught by North American tango legend Daniel Trenner. With Trenner's help, they returned to Eugene to initiate formal lessons and weekly practicas, providing ann invigorating pulse for the expanding tango scene.

“We started the first year with three people. By the end of the first year, there were 15 to 20 that came on a regular basis,” says Wartluft. “After two years, there were about 20 to 25. It’s been feeding now for 10 years.”

Today, aspiring tangoistas can find a venue for dancing virtually every night of the week. Series classes are held at the UO Dance Department; drop-in classes and practicas are held at Studio B; regular milongas take place at the World Cafe and at The Buzz Coffeehouse on campus. The Tango Center hosts all three categories.

“There are so many different venues and styles of tango in town,” says Lane Community College tango instructor E. Vivianna Marcel. “There's literally something for everyone.”

A Cultural Mélange

A rich tapestry of music wafts out of the Tango Center over the wet pavement down-town. The strong march of the Bandoneon beckons pedestrians to investigate the strange call to dance. As they stand transfixed in the doorway, a piano invites them inside, where they discover the source of the unfamiliar sound: a laptop sitting on a simple folding table. There, from its perch, it doictates the syncronized whirling of dozens of couples on the dance floor. There's only one leader in tango, and it's the music.

Photo by Jeff Parker: Dominic Bridge and Alycia Smith lead a UO beginner class.

Born in Buenos Aires in the late 19th century, tango was first danced among displaced gauchos in the city's slums and brothels. Traveling tango performers in Paris prompted the first international tango craze in the early 1900s, finally reaching the United States in 1912. Although the dance was denounced as immoral by the Vatican in 1914, tango flourished. Into the 1940s, it was the quintessence of Latin American exoticism and sensuality.

During the era of the Perón government and military rule following World War II, restrictions on public gatherings, coupled with the popular influence of rock 'n' roll, led to the death of tango for an entire generation of Argentines. It wasn't until the return of democracy in 1983 that stage productions such as Tango Argentino (in Paris) and Forever Tango (in New York City) revived the dance's international allure.

“In the last 20 years it's like an explosion of tango,” says Tango Center instructor Marisela Rizik. “You go to Europe and you find tango. You go to almost any city in the U.S. and you find tango. It's really pretty amazing.”

Vicky Ayers is among the Eugeneans who fell under tango's spell early. She has been dancing for 10 years.

“I knew nothing about tango," she recalls. “I was sitting in a café in Argentina, having lunch with a friend, and in the middle of it she pushed her chair back and belted out this gorgeous song, and everyone in the café sort of paused and looked at her, like, ‘No big deal’. When she was done, they all went back to their meals. I thought, ‘Wow, I need to know more about this!’ It was the music that pulled me into tango.”

Like Argentina’s national heritage, tango music is a montage of African, Caribbean and European influences. It is traditionally performed by a sextet consisting of a double bass, a piano, two violins and two bandoneóns, or “button accordions” that arrived by way of Germany.

“It was music I was unfamiliar with,” says Ayers. “It's so haunting and unusual. I mean, it's simple and keeps a steady beat, but on top of that there are all of these little yummy parts, little adornments. And the bandoneón just pulls you in. It's the sound of breathing, but melodic breathing."

All in the Footwork

Dancers filter in to the studio, alone and in pairs. They scout out tables to store their things and don their dancing shoes. You can almost invariably distinguish a dancer's level of experience by his or her footwear. Beginners sport street shoes -- sneakers, sandals, even flip-flops. Intermediate dancers wear generic dance shoes -- jazz flats or leather-soled character shoes for ladies, casual dress shoes for men.

Perhaps the most common attraction to tango derives from its enigmatic movement and intricate footwork. Professional tangoistas perform breathtaking combinations that have given the dance both a spectacular allure and a reputation for being among the most difficult partner dances in the world.

For most dancers, though, tango consists of varying levels of complexity, making it accessible to beginners, veterans and dancers of all ages. Its improvisational nature also lends it an air of experimentation and the illusion of infinite possibility.

“Greg Estes once said, ‘There are no mistakes in tango, just unforeseen outcomes,’” says LCC's Marcel.

Soon the most experienced dancers arrive. Men lace up shiny, leather-bottomed dress shoes and women display flashy high heels of every color and variety -- black patent-leather T-straps with decorative cutouts, red-velvet stilettos, toeless gold-and-silver heels with straps that wrap like vines around their ankles. Mesh-toed, diamond-studded and sparkling, they're ornaments to an inherently flamboyant dance.

The roots of tango's powerful and expressive movement lie in the fusion of Argentina's indigenous, immigrant and slave heritages. Its ancestors include the Cuban habañera, the Italian tarantella and the South American milonga, which was heavily influenced by African dances that were brought to the continent during the slave trade.

The original tango, organic and improvisational, was simplified and packaged for an American audience in 1914 by tango pioneers Vernon and Irene Castle. This version became known as the American tango, and has achieved its own popularity on classical ballroom floors. To dancers of the authentic Argentine version, however, it's an entirely different dance.

“It would be like taking hip-hop and then trying to break it down and sell it -- like, these are the five steps to hip-hop,” says Vicky Ayers. “American tango doesn't have a culture. It doesn't have a base.”

Photo by Jeff Parker: UO tango instructor Vicky Ayers and her husband, Tom, demonstrate for the class.

Fundamentally a walking dance, tango consists of a series of interlocking footsteps, randomly punctuated by fluid turns, dramatic pauses and interludes of rocking back and forth, to regain connection. The movement itself is challenging, due both to its intimacy and to the precision it requires for the leader and follower to communicate, without words, on the dance floor.

“If you're a really good tango dancer, you should be able to dance with anybody. But it's a really hard skill,” Elizabeth Wartluft says. “It's very vulnerable. You have to open your body up in this dance. You can't wall off someone emotionally, because you can feel it in the dance."

Marisela Rizik agrees. “When you get to a certain point in tango, it's like a meditation, where the follower can close her eyes," she says. “And that's what I think fascinates some people—that for three minutes of a song, you are so close to someone else that you've never met in your life, and you don't care.”

The Last Dance

By 11 p.m., the Tango Center is packed with dancers of all ages. A young girl lies curled up on a couch, eyes closed, as her parents relish one last dance. Members of the UO Tango Club sit sprawled on the floor, laughing and talking, until a particular song beckons them to the dance floor. Even the oldest dancers have no trouble keeping pace with the lively crowd.

During a Sunday afternoon beginner lesson at Studio B, a dancer who refers to himself only as Grandfather Johnson escorts his partner around the second-story dance floor. He's “in his 60s” and has been tango dancing for just over nine months. He says he enjoys the exercise, the social outlet and the challenge of learning something new.

“Beginning teachers lie,” he chuckles. “They tell you all you have to do is walk. They also tell you there are no mistakes, only embellishments and adornments. The truth is, tango is not that easy.”

Lisa Young and Rochelle O'Bryant, 15year-old students at North Eugene High School, have been coming regularly to the Tango Center since August. They have a slightly more popular interest in learning the dance.

“We used to always watch these musicals, like Moulin Rouge and Chicago, and they have these amazing tango scenes," says O'Bryant. “I just always wanted to try it.”

Among the more experienced dancers who frequent the Tango Center are Judith Bedford and Jean-Paul Baarsma, who commute from the Medford area. They fell in love with tango, and with each other, in a beginner class two years ago. They've been dancing virtually every day since.

“I love the spiritual connection that I have with the dance,” says Bedford. “In a time when women wear so many different hats, it's an opportunity to let go and be led.”

Baarsma, who has a martial-arts background, describes it as South America's contribution to the Zen mind. “A man finds his gentler side doing this dance," he says. “It absolutely destroys your ego.”

As the night wears on, the dance floor begins to empty. By 1:30 a.m., only a few tired but dedicated couples remain. Their movements are less bold now, even sleepy. It's as if the dance, once glamorous and showy, has been boiled down to its essence: the intimate connection between two dancers whose very breathing suggests movement.

“I think that couples' dancing is something we've lost in our culture,” Wartluft says. “Tango helps you communicate with a partner on a level that we don't tend to know. We talk on our cell phones, and we have our MP3 players on when we walk around. We don't interact at the same level as people have for centuries, and I think that dance is a good skill to have -- not only to meet other people, but just to be face to face for a couple of minutes and not tune out.”

EUGENE MAGAZINE • WINTER 2006 - 2007

Where to tango in Eugene

Tango Center 194 W Broadway; 541/349.8682, www.tangocenter.org Studio B 189 W 8th Ave., 541/349.8682 World Café 449 Blair Blvd.; 541/485.1377 UO Dance Department Gerlinger Annex (east side of Knight Library) 541/346.3386, http://dance.uo.edu The Buzz Coffeehouse UO Erb Memorial Union E 13th Ave. and University St.; 541/346.0590, http://emu.uo.edu [All of the details above are now out-of-date -- 2022] For more information about local tango lessons and events: www.eugenetango.com.